Mónica Ribadeneira Sarmiento (ELP 2014) | Prindex Regional Engagement Coordinator Latin America, Global Land Alliance, Ecuador

One of the mottos of the UN World Food Systems Summit 2021 was “let's build a just world where no one is left behind,” but the truth is that all people and families without clear land rights are already behind.

The food which arrives at our table every day is produced by small farmers, agricultural workers, and indigenous peoples who are poorly paid and badly recognized. In most of the cases they are not owners of the land they use to cultivate; moreover, their tenure insecurity is so high that they fear eviction.

According to the International Land Coalition (ILC) family farms occupy around 70-80% of farmland and produce more than 80% of the world's food. For them and for some others, land is not just an asset or an article of trade or commerce, it has a cultural significance, heritage and meaning, and it is a key element of their identity, sense of dignity, and wellbeing. Simply: it is home.

Property rights are a cornerstone of economic development and social justice, in areas such as food security that have been left aside and where the links between them are not properly recognized in public policies. It would be impossible to achieve good land governance if property rights are not included as a key element.

Chimborazo, Ecuador. Source: M Ribadeneira Sarmiento (2021)

When Prindex conducted surveys in 140 countries and asked people how sure they feel about their rights, the findings took your breath away: 1 billion people around the world live in fear of losing their home or land. It means that worldwide 1 in 5 people living in rural areas feel insecure about their land rights. The rates of insecurity vary widely around the world: it is higher in South and East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Since the Prindex free database was launched, it has become a tool for local and national authorities to define public policies to attenuate the land insecurity of the people.

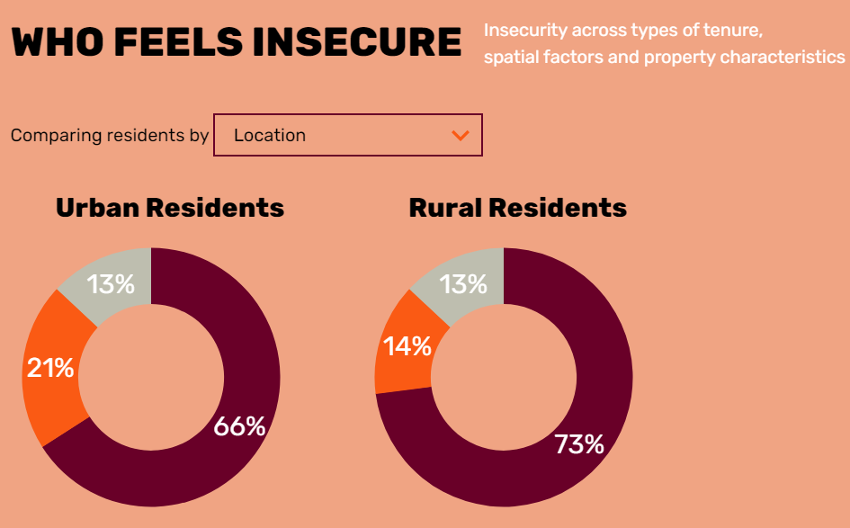

Prindex gives important information about any of the 140 countries studied in three main areas: (i) levels of insecurity; (ii) who feels insecure, and (iii) why people feel insecure. It is also possible to get deep information on these matters, for instance within the question "who feels insecure" there are eight main demographics: location, ownership, gender, age, income, type of documentation, number of properties, and employment status. The following example is the answer to the question "Who feels insecure” in comparing residents by “location" in Honduras.

As it is shown, in Honduras the rural residents feel more insecure than urban residents; there are 7 points different of insecurity. These people include rural workers and indigenous peoples, many of them disenfranchised women or abandoned single mothers.

Urban and Rural insecurity levels - Comparison of Honduras information by location

Source: Prindex (2020)

The starting point to talk globally about food systems was the information from the UN’s 2021 report on food security, it stated that 928 million people are living with severe food insecurity around the world and this number will increase to 118 million. The Food Systems Summit was a global call to offer up the kind of structural overhaul the world needs.

During the Summit the world heard presidents, high level delegates from UN system and famous people asking and presenting commitments to transform the food systems; some of them are quite significant such a Burkina Faso's promise to include the right to food in its Constitution, and also the announcement made by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation regarding of a five-year funding of 922 million dollars for global nutrition.

Nevertheless, there were basic commitments the world did not hear.

It is well known that stronger land rights – especially for women – increases the wellbeing of families, decreases social conflicts, prevents migration and displacement, and assures better market conditions for rural production.

The world did not hear any commitments in this regard.

Also, no mention was made about farmers, youth, and indigenous needs including their land needs, need for working capital in fair credit conditions, and protection from unfair markets.

Indeed, it is very simple: they need to be protected to continue feeding the planet. It has been pointed out before: at the top of the Summit's agenda had to be the human rights approach which includes stronger land rights for indigenous people, women, small farmers, and workers. Evidence shows that where food producers enjoy secure land tenure, they invest more in their farms for the long-term, resulting in productivity gains and less pressure on the land.

Unfortunately, at the end of the day, the Food Systems Summit did not hit one of the most elemental problems regarding food security: rural property rights and security on rural land tenure.

Nowadays it is left to us to continue pressing to give voices to small farmers, agricultural workers, indigenous peoples, and rural women, mainly to point out the critical importance that land rights have to these vulnerable groups. It is our duty to discover how, in our daily job, we can develop innovative initiatives that assure property rights for these vulnerable groups. Our goal is to have (for our and future generation's well-being) public policies that focus on land and human rights for the people who are feeding us, and asking almost nothing for their effort.

If we do not do that, millions of people will be left behind.